Interlinear Translation of the Month #38

The Study of Islamic Interlinear Texts from Indonesia

October 2025

Ronit Ricci

Within the context of Textual Microcosms, a research group studying interlinear translation across the Indonesian-Malay world, this blogpost briefly explores the following question: how was the phenomenon of Islamic interlinear translation in Indonesia studied by scholars of earlier generations?

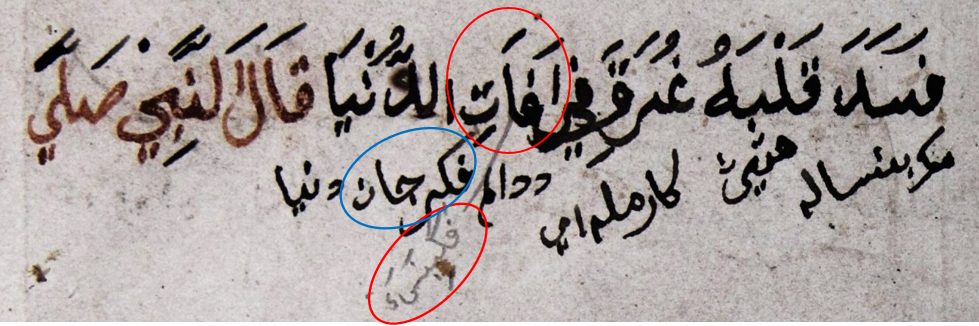

Before asking “how was interlinear translation studied,” we might do well to wonder whether it was a topic of investigation. We know that some of the earliest extant manuscripts from the region are in the form of interlinear translations from Arabic to Malay (al-Attas 1988; Drewes 1955) and Arabic to Javanese (Arps and Gallop 1991, see Figure 1), and it is also known that there are numerous such manuscripts in libraries and private collections in Indonesia and abroad, thus it is clear that interlinear texts have been around for a long time and in large volume. Was this richness matched by the attention devoted to the phenomenon in the scholarship?

are in the form of interlinear translations from Arabic to Malay (al-Attas 1988; Drewes 1955) and Arabic to Javanese (Arps and Gallop 1991, see Figure 1), and it is also known that there are numerous such manuscripts in libraries and private collections in Indonesia and abroad, thus it is clear that interlinear texts have been around for a long time and in large volume. Was this richness matched by the attention devoted to the phenomenon in the scholarship?

Figure 1. Masāʾil al-taʿlīm, Arabic with Javanese translation and notes, 1623. British Library, Sloane 2645

In what may be one of the early mentions of interlinear translation in a scholarly publication the famed Dutch linguist Van der Tuuk, writing in the Leiden-based journal Bijdragen tot de taal-,land- en volkenkunde (BKI) in 1866, mentioned an Arabic to Malay interlinear translation of al-Samarkandi’s Bayān ʿaqīdah al-uṣūl (commonly known in Indonesia by its author’s name) in a brief report he published on various Malay manuscripts. There was no detailed description or discussion, but Van der Tuuk was clearly familiar with this popular text and noted that interlinear translations of al-Samarkandi into Javanese in west Java were “numerous” and that there was also, in Batavia, a commentary on the text which had an interlinear translation in Javanese. Finally, he mentioned that he was in the possession of two such commentaries in Sundanese. Based on this fleeting note we can conclude that Van der Tuuk was familiar with the phenomenon, with interlinear translations from Arabic into two or three languages (Malay, Javanese, possibly Sundanese), and with their popularity. There is nothing in his brief paragraph that expresses any surprise or special interest or insight.

Fifteen years later (1881), writing in the same journal, the philologist A. W. T. Juynboll discussed an Arabic to Javanese interlinear translation of the same text, which he had translated into Dutch. His article, which contained only two pages written by him and ten pages of the interlinear text, was titled “A Muslim catechism in Arabic with a Javanese interlinear translation in pegon script.” All we learn about the manuscript on which his translation was based is that it was brought by one of his students from Java to Holland, and that large parts of it were eaten up by ants. Although Juynboll highlighted the interlinear translation in his article’s title, he seemed interested in authorship, content and textual versions but said nothing of the translation method, its uses or implications. The Dutch translation he produced referred only to the Arabic text, ignoring the potential meanings and nuances of the Javanese interlinear translation and its use as a pedagogical and cultural phenomenon. Although this remains unacknowledged, the Dutch in fact replaced the Javanese as the translation language.

This type of approach, which viewed interlinear translation as a gateway to questions of content and textual variability but not necessarily as worthy of study in its own right as a translation model, as a pedagogical tool or as a product of a particular culture, seems to have been common amongst colonial scholars in the 19th and early 20th centuries. However, although less common, a different approach was also evident at the time: the work of Van Ronkel stands out for his interest in the translational practice itself and his attentiveness to the detail that is among the hallmarks of interlinear translation. In an 1896 article describing six manuscripts housed at the Cambridge University library he discussed two that included interlinear texts and commented in detail on several of their characteristics. Possibly following that work, as well as an examination of additional manuscripts he encountered, Van Ronkel several years later (1899) published what constituted (and still does) a pioneering attempt to survey the interlinear practice and map its far-reaching effects. Some of Snouck Hurgronje’s work also reflected an interest in the nuances of interlinear translation.

In general, a broader survey of 19th and early 20thc. literature on Islamic interlinear translation, which is beyond my scope here, shows that the popularity of this practice was not matched by the scholarship produced about it. What can we glean from this fact, and from the approaches presented, however tentatively? Can we detect in the lack of interest, as has been more generally proposed regarding colonial Dutch scholarship, a bias towards the Hindu-Buddhist and away from the Islamic? The curiosity or lack thereof towards interlinear texts may have been part of the trend, i.e., an enduring interest in the ruins of temples, ancient sculpture, the role of Sanskrit in Old Javanese poetry, while viewing Islam as a “thin veneer” covering prior traditions and possessing a deep-seated anxiety about Islam. It may have also been that interlinear translation was taken at face value, as a convenient way to translate – to transfer meaning efficiently from one language to another – but no more than a technical device. Scholars of the period who were exceptions to the rule in their interest and in the studies that they produced, above all Van Ronkel and Snouck Hurgronje, showed how those who did examine the practice of Islamic interlinear translation more closely discovered its complexity and its implications which were apparent in the linguistic, religious and social spheres. The work of these scholars (and other, more recent ones whose studies lie beyond the scope of this blogpost) points to the richness of interlinear translation as a research topic and to the many yet unanswered questions about it that await investigation.

References:

Al-Attas, S. M. N. The Oldest Known Malay Manuscript: a 16th Century Malay Translation of the ‘Aqa’id of Al- Nasafī. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya, 1988.

Arps, B. and Gallop, A. T. Golden Letters: Writing Traditions of Indonesia/Surat Emas: Budaya Tulis di Indonesia. London: The British Library; Jakarta: Yayasan Lontar, 1991.

Drewes, G.W. J. Een 16de Eeuwse Maleische Vertaling van de Burda van al-Busiri (Arabisch Lofdicht op Mohammad) ‘s-Gravenhage: Martinus Nijhoff, 1955.

Juynboll, A.W.T. “Een Moslimsche catechismus in her Arabisch met eene Javaansche interlineare vertaling in pegonschrift.” BKI 29 (1881): 215–227.

Ricci, R. “Interlinear Texts from Indonesia: Preliminary Thoughts on their Study.” Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies (forthcoming 2025).

Van der Tuuk, H. N. “Aanteekeningen.” BKI 13.1 (1866): 466–467.

Van Ronkel, Ph. S. “Account of Six Malay Manuscripts of the Cambridge University Library.” Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde 46, 1 (1896): 1–53.

Van Ronkel, Ph. S. Mengenai Pengaruh Tatakalimat Arab Terhadap Tatakalimat Melayu. Trans.Ikram, Jakarta: Bhratara, 1977. First published as “Over de Invloed der Arabische Syntaxis op de Maleische,” Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal- Land- en Volkenkunde 41(1899): 498–528.

Figure 1: Example of a Balinese lontar manuscript from the Lontar Library of Udayana University.

Figure 1: Example of a Balinese lontar manuscript from the Lontar Library of Udayana University.

Figure 2: A page from Kekawin Arjuna Wiwaha Maarti (here “Kekawin” reflects the Balinese form of the Old Javanese kakawin), showing the Balinese translation aligned with the Old Javanese source text by dotted lines. Courtesy of Balai Bahasa Provinsi Bali.

Figure 2: A page from Kekawin Arjuna Wiwaha Maarti (here “Kekawin” reflects the Balinese form of the Old Javanese kakawin), showing the Balinese translation aligned with the Old Javanese source text by dotted lines. Courtesy of Balai Bahasa Provinsi Bali.